Self-advocacy for autistics

Resources and advice to support you in accessing adequate mental and physical health care and treatment in autistic perimenopause

Content warning: there are references to self harm, suicidal ideation and suicidality. Please only read on if you feel okay with this content today, and take care of yourself.

By the time we reach midlife, autistic women have been socialised to not take up space, to minimise our own discomfort and to mask our differences. We go along with this to make ourselves more acceptable to others, and to just fit in socially. However, this only serves others, and is an enormous disservice to our own mental health. Learning to self-advocate in midlife is an essential skill to build, particularly as autistic perimenopause may be eroding and regressing your other skills, whilst causing significant distress.

It is time for us to rise up and have our voices heard. I know that is a sweat-inducing prospect - even ringing for a doctor’s appointment can be stressful enough, never mind actually having to attend in person, and list all your embarrassing symptoms. Thanks to growing up in this misogynistic patriarchal society, we already have to battle against medical misogyny where women’s health is little understood, and treatment can be subpar.

Our generation is pushing back hard against this, and perimenopause is no longer in the dark. The odds are in our favour, as female autism and menopause are gaining public awareness. It is our collective responsibility to keep pushing the agenda forwards and increasing knowledge on autistic perimenopause, by speaking out, and getting support as and when we need it. Let’s drop the shame and the guilt. Autistic perimenopause can be lethal when our mental health is ignored and suppressed. This isn’t a fluffy self-care commercialised notion - we require healthcare to sustain our mental wellbeing throughout midlife and beyond.

Autistic midlife women are susceptible to suicidality, and this increased risk needs to be managed so that we can survive the menopausal transition, and thrive as we age. We all know knowledge is power, and we need to remember too that disinformation is disempowering. It is essential that we use the (limited) academic research on autistic perimenopause to make gains individually. We need to trust that our self-advocacy will pay dividends when speaking up for ourselves, because it also means we are speaking up on behalf of everyone in autistic perimenopause.

Self-diagnosis/self-identification is valid and necessary when identifying as autistic later in life. A formal diagnosis is a luxury many can not afford, and the public health systems have led to many women being repeatedly misdiagnosed with other health and psychiatric conditions.

Women who retrospectively notice patterns in periods (excuse the pun) of enormous or more subtle hormonal shifts over their lifespan to date (during puberty, menstruation, use of hormonal contraceptives, pregnancy, post-natal, breastfeeding, perimenopause) are not imagining it. Self-reports made in hindsight of cyclically significant mood dysregulation and sensory overload, with increased meltdowns/shutdowns, are enough to present to a doctor, and expect to be taken seriously. If you didn’t tolerate the contraceptive pill and/or felt your mood was unstable during puberty, this is a risk factor for post-natal depression. Post-natal depression is a risk factor for perimenopausal depression. For autistic women who are not parents, reflecting on your mood during menstrual cycles can also help you self-identify your risk in perimenopause.

Why does this matter? Because autistic women are at increased risk of suicidality in midlife, and we need to work together to reverse this trend. Autistics are true pattern seekers and pattern spotters - we can see autism in others so clearly, but it is harder to see in ourselves. It can be equally hard to spot perimenopause, instead wrongfully assuming we are losing our minds. This is easier to believe in light of all the previous misdiagnoses we may have received to date.

So what does the research into autistic perimenopause tell us?

“A key takeaway is the importance of person-centred, autism-informed healthcare that considers intersectionality and accessibility needs. We encourage healthcare professionals to recognize autistic communication styles and the various symptoms of menopause, including those that are less widely discussed, and to be receptive to the fact that menopause may start earlier than is commonly expected. The reported range of estimated menopause onset was 38–51 years, and some participants reported that doctors had not recognized or believed their symptoms of perimenopause as they perceived the participants to be too young to be in perimenopause.”

No surprises there - medical misogyny and systemic ableism are rife - but it is still stark seeing it written down in evidence-based research. No, you are not imagining it when you feel dismissed and patronised by your doctor. It is not their fault either; their training has not provided them adequate training to support female autistics, nor perimenopausal women. Thus autistic perimenopausal women presenting to a doctor may not be understood, validated nor reassured.

It is important that you work with a doctor whom you trust has your best interests at heart, and is willing to work proactively with you. Self-advocating is best received by a doctor who you find validating. They don’t need to have all the answers, but they do need to make you feel emotionally safe, and listened to.

In this previous piece, I have listed some general rules I follow when choosing a doctor:

Ten steps to get help and survive the worst days/weeks/months/years of autistic perimenopause:

Self-advocacy suggestions for medical appointments:

You can take a support worker/friend/relative to advocate for you, just to accompany/chaperone you, and/or to scribe during the consultation.

You can pre-plan your script in your head and/or take in notes as prompts to discuss.

You can give the doctor some information sheets etc. you have accessed online (links shared below). As long as they are from reliable medical sources, the doctor may find this beneficial. It is pretty frustrating though to have to use our limited capacity educating healthcare professionals.

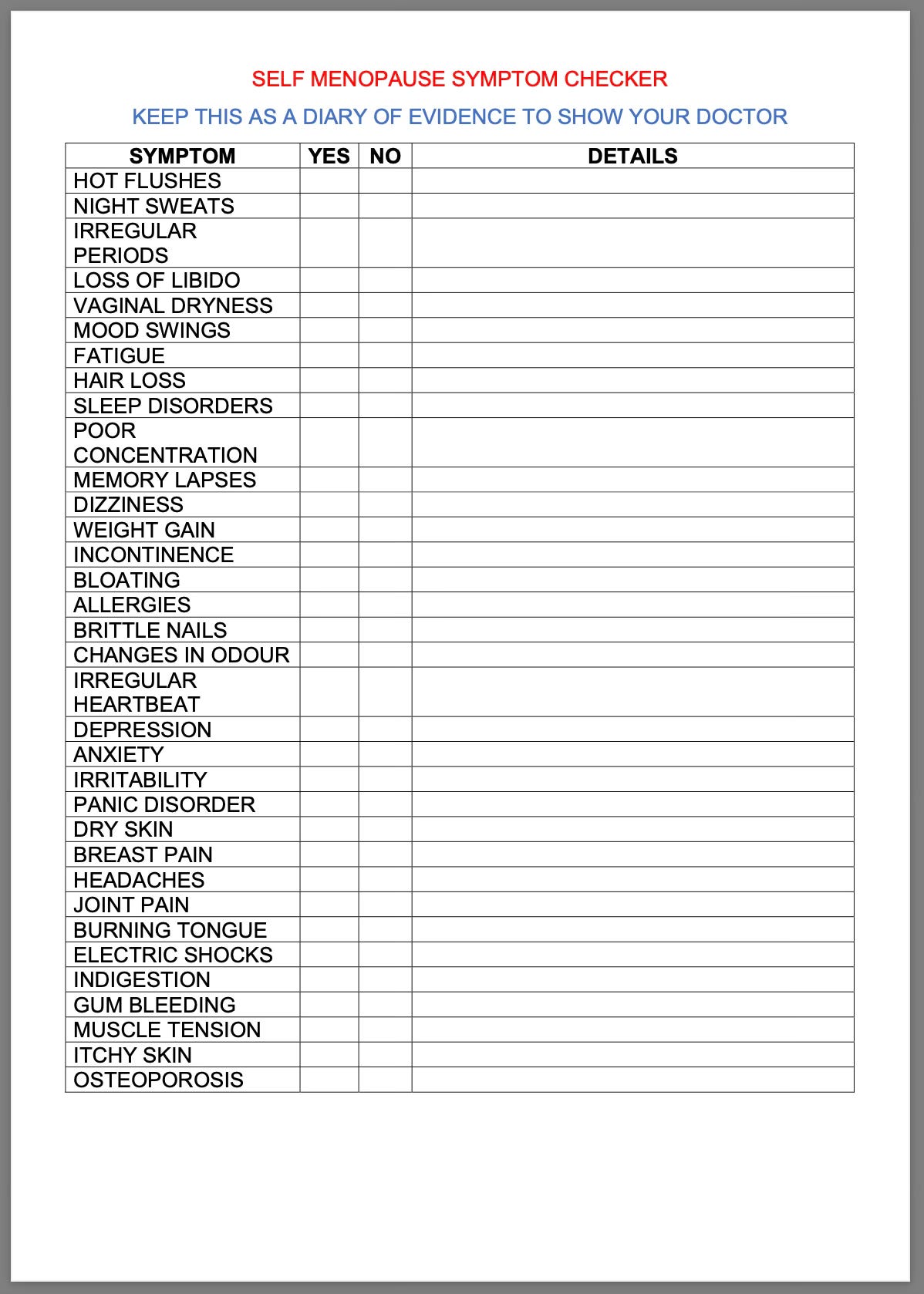

You can complete self-assessment reports and symptom checklists (links shared below) in advance to inform the consultation, and take the pressure off you needing to rely on speech/working memory to convey your current state and symptoms.

Anticipate cliched responses such as “You’re too young to be perimenopausal”, and respond as calmly as possible. Breathe!

You can ask permission to voice record the consultation, and then use AI to transcribe it for you to review and process at home in your own time.

Don’t be afraid to take up space and time, your health is important to everyone.

Your doctor is employed to help you, but they may not yet know how best to do so.

Request Telehealth consultations, if preferred. Your doctor may have an online portal with which they can message you if this is preferable to face to face spoken communication. Emails and texts may also be an option.

Request that information be presented to you visually, and that you are given adequate response/decision making times.

Please know that getting support and treatment now can prevent future/further regressions to your functioning and capacity.

Focus on your long term health goals where possible in all your decision making. How do you want to feel in six months/one year/five years, and what individualised treatment will best help you achieve this?

Know the side effects of any medications or hormonal replacement therapy/menopause hormone therapy (HRT?MHT). Anticipate having the side effects and plan around them so you can cope while adjusting to new medications.

As far as you feel safe in doing so, unmask with your doctor and medical team so they are fully aware of the challenges you are facing. Be honest with them. Hiding the extent of your struggles will not benefit you nor anyone else in the long term. (Sorry, I know this is horrible and makes us feel so vulnerable, but your medical team can only support you if they know how bad things are. They do not want to stigmatise you, shame you, nor take your kids away from you.)

Go along with a plan in mind, but be flexible and open to their suggestions and recommendations.

If you don’t feel seen or validated, you are fully entitled to seek a second opinion and/or request a referral to see a specialist.

Discuss your mental health history with them. Identify and highlight patterns around hormonal shifts/cycles. Tell them if you have experienced suicidal ideation, self harm or have attempted suicide. Request a referral to adult mental health services if you need to. It is essential to have a suicide prevention plan (links shared below).

Recommended resources:

In a recent post I compiled the best of autistic perimenopause resources here:

The following resources are general perimenopause resources, and autism resources.

The Australasian Menopause Society provides information for doctors and other health practitioners in supporting women through midlife health and the menopause.

The Information Sheets have been organised into the following management areas for ease of reference: menopause basics, treatment options, early menopause, risks and benefits, uro-genitary, bones, sex and psychological, alternative therapies and contraception.

They also have more basic fact sheets for patients, but the information sheets will give you more comprehensive information, helping you feel informed when discussing with your doctor.

Here are the alphabetised doctor’s information sheet titles:

The Australasian Menopause Society also has online Self Assessment Tools: “Information and tools to assist in understanding and assessing risks factors for bone health, breast cancer and cardiovascular disease.”

The NHS has provided this general self menopause symptom checker, which the pedant in me would like to change to “menopause symptom self checker”. (Stay in your lane, Sam.) It is a useful resource that can be printed out and taken/emailed to inform your doctor appointments. It would also be useful to update over time as symptoms change in type and/or severity.

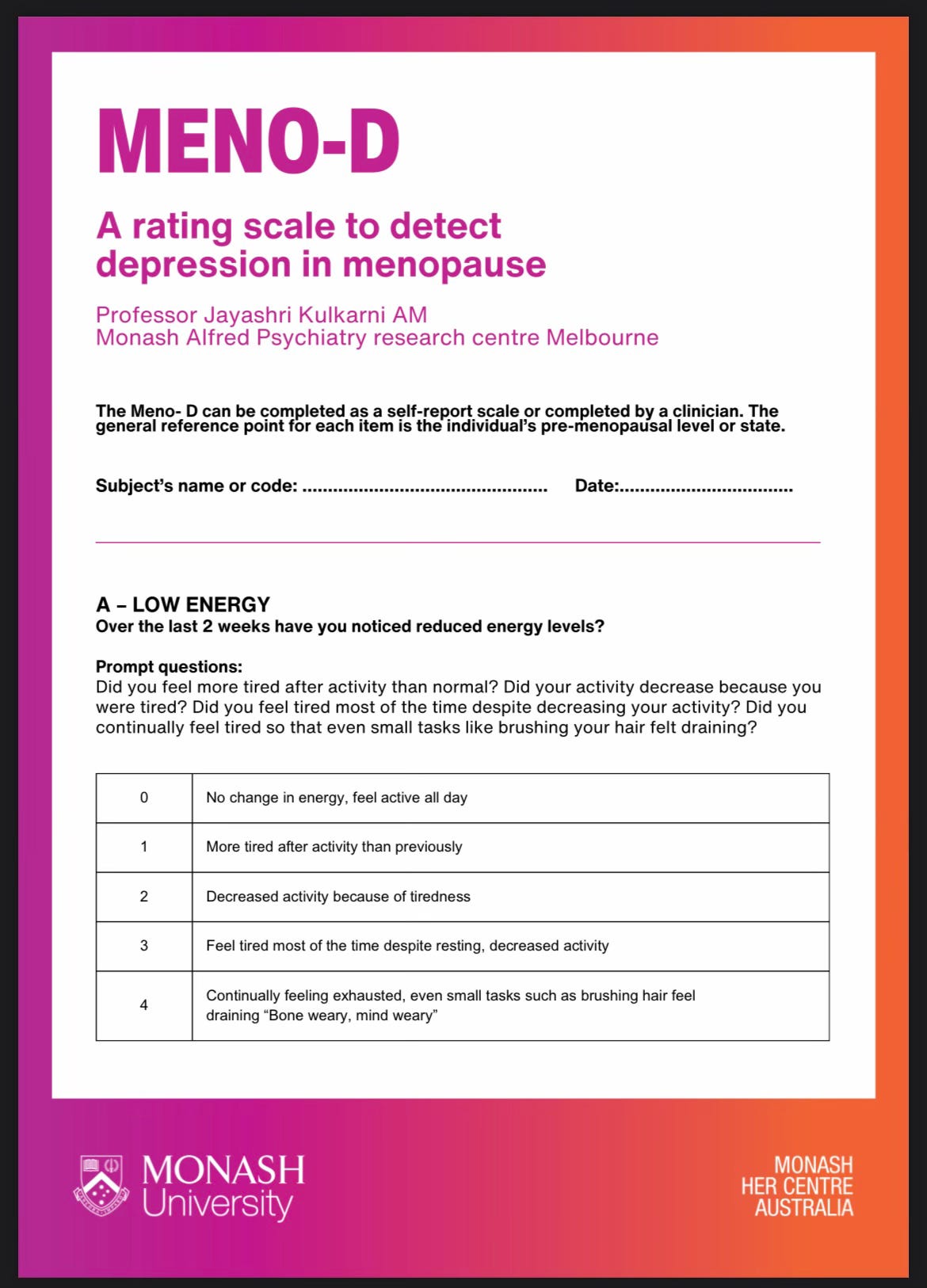

Monash University has developed Meno-D - A rating scale to detect depression in menopause, and can be completed as a self-report or completed by/alongside a doctor. This can be completed regularly and the scores tracked to support women as their hormonal fluctuations alter their mood and overall functioning.

This Glossary of Terms, from the AMS is a useful document that provides definitions that may be used by doctors regarding menopausal treatment and care. It is intended for health professionals, but will be useful to everyone involved in your care, including you.

This AMS training video for GPs (56 minutes) can give you a good level of knowledge before you see your doctor. You may also like to forward it to them. Could this be menopause? - A practical approach for the busy GP

“A panel of experts presented a selection of cases and discussed validated diagnostic tools and evidence-based management options.”

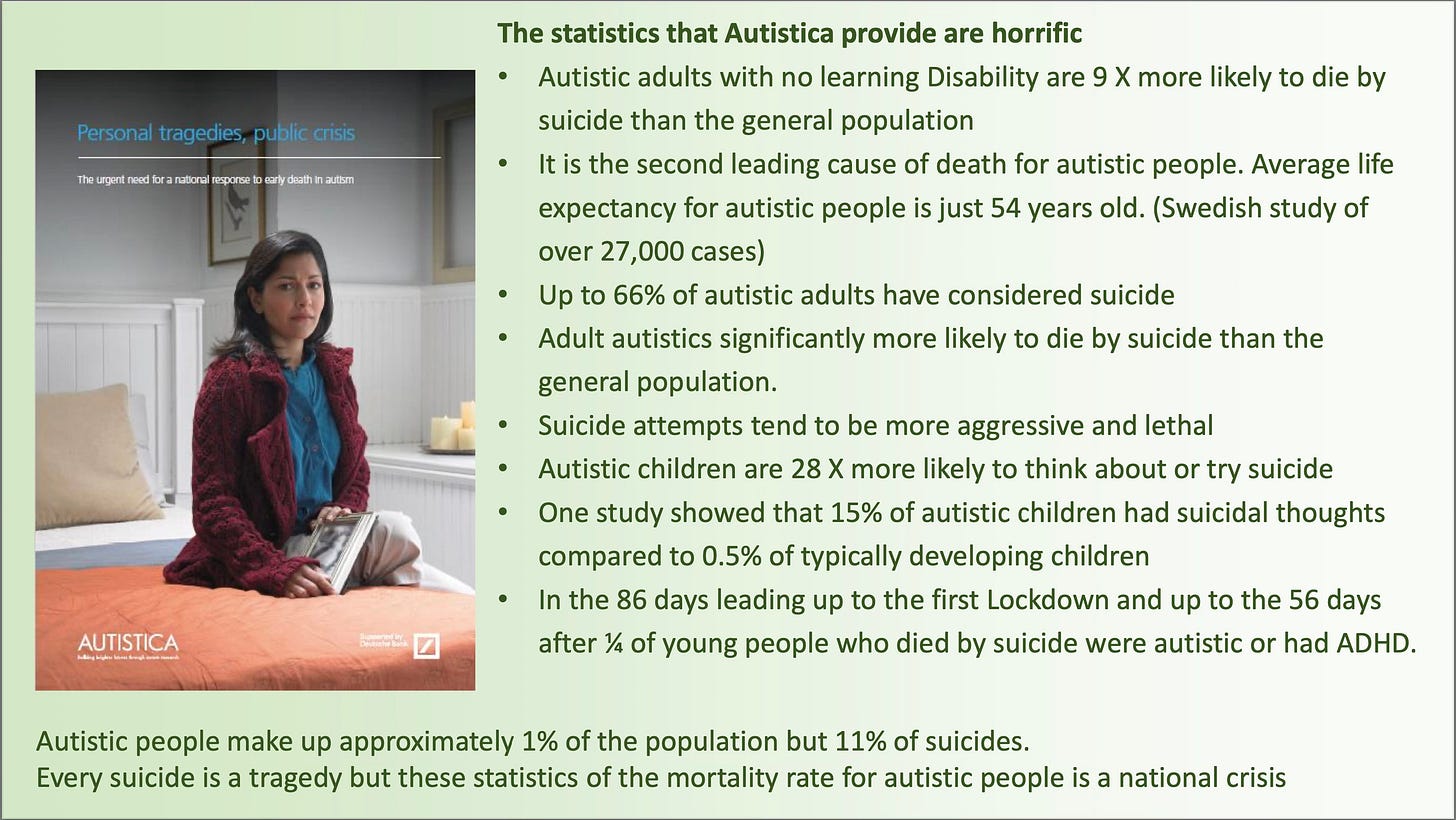

Suicide and Autism, a National Crisis (UK)

We all know that mental health is fragile for autistics. We are a vulnerable community and we require and deserve specific support accommodations. Midlife is an especially difficult time for neurodivergent women. For many of us, suicidal ideation recurs through hormonal transitions and fluctuations. Just because we learn to anticipate it doesn’t mean we can afford to desensitise ourselves from this very real risk of harm and fatality.

Why did we develop autism adapted safety plans?

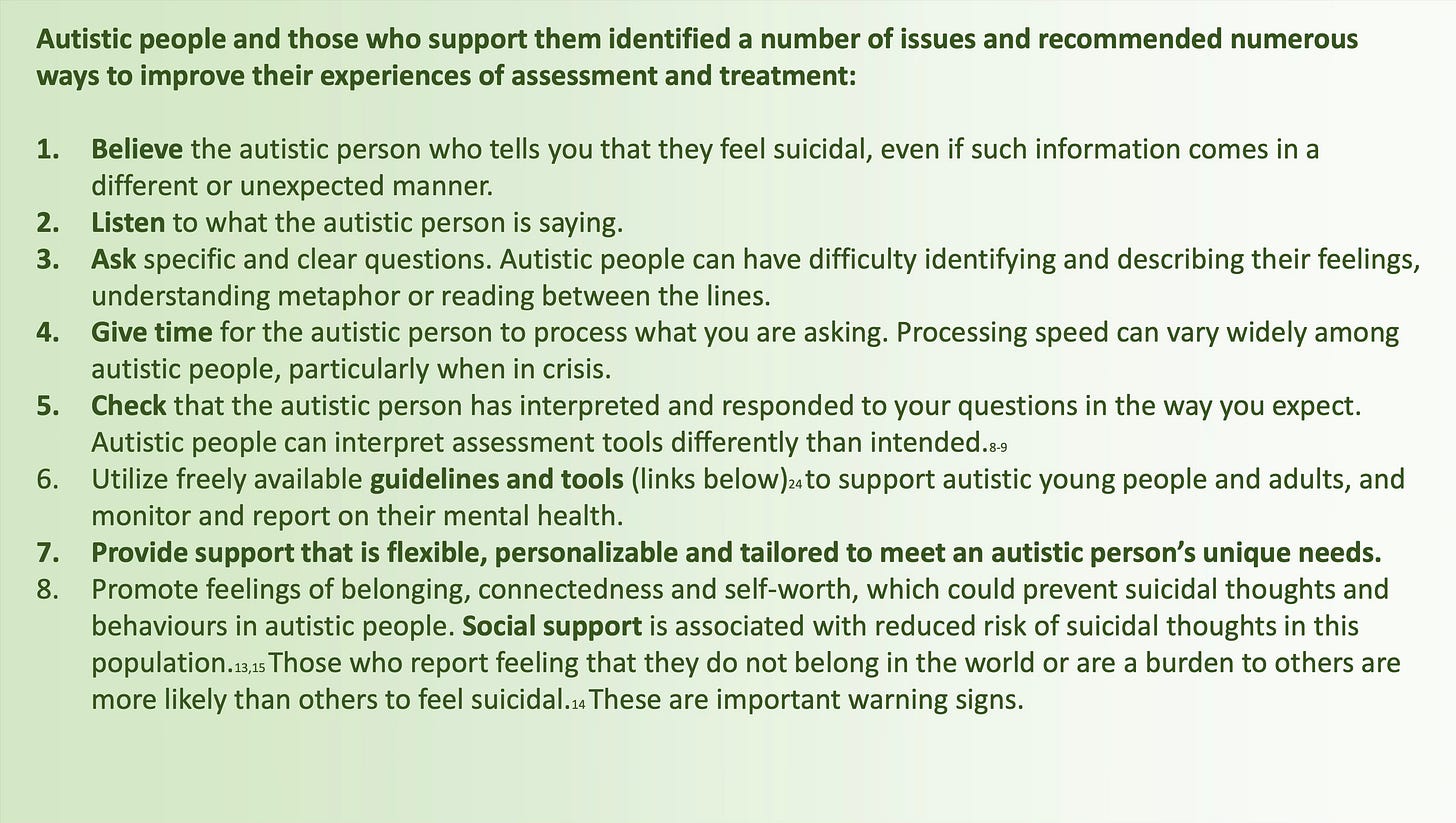

Research shows that autistic people are more at risk of self-harm and suicide than non-autistic people. However, there are no suicide prevention interventions which have been developed specifically for autistic people. Developing personalised suicide prevention interventions with and for autistic people is a top research priority identified by the autism community. Safety plans have been shown to reduce risk of self-harm, suicidal thoughts and behaviours in a range of different groups. Safety plans have also been suggested as a potentially useful personalised suicide prevention intervention by autistic adults and those who support them.

What are safety plans?

Safety plans are prepared by a person at risk of self-harm or suicide before a crisis. The plan describes a series of steps a person can follow to help keep themselves safe when they feel the urge to self-harm or end their life. Safety plans are personal and need to be written in the persons own words. A person can develop a safety plan on their own, or with the support of a trusted person if they wish. This trusted person can be a friend, family member, support worker or any other professional.

What is an autism adapted safety plan (AASP)?

We conducted a series of studies to:

1) Adapt safety plans with and for autistic adults and those who support them;

2) Explore whether our autism adapted safety plans were acceptable and useful to autistic adults and those who support them.

We found that safety plans need to be adapted to meet the unique needs of autistic adults. Many autistic adults needed the support of a trusted person to complete the safety plan. Safety plans needed clearer instructions, examples and resources to help autistic people successfully complete a safety plan. Some sections needed rewording or adding to make them clearer and more relevant to autistic people. We found that a majority of autistic adults and those who support them were able to complete an autism adapted safety plan, and found their safety plan useful.

Autism adapted safety plan (AASP) - link to PDF version of an autism adapted safety plan and supporting materials. The resources are suggestions to help you understand and complete the safety plan for yourself, or to support another person to complete their safety plan.

Step 1 - What are my warning signs that I may start to have strong thoughts, feelings or urges to hurt myself and/or end my life? (e.g., reduced enjoyment in a strong interest, change in routine, change in patterns of sleep, eating, mood)

Step 2 - What can I do to help distract myself? (e.g., engage in a particular activity or interest, a relaxation technique, or physical activity)

Step 3 - People I can contact to ask for help: (e.g., family, friends, mentor, support worker). Remember to note down when people are, or are not, available (e.g., office hours).

Step 4 - Professionals or agencies I can contact during a crisis: (e.g., Samaritans, Mind, A & E, Psychiatric Services). Remember to note down when people are, or are not, available (e.g., opening hours).

Step 5 - What can I do to make the environment around myself safer? (e.g., throwing away things that could be used to harm yourself)

Step 6 - How can other people help support me?

How do I communicate distress? (e.g., I shut down, I have a meltdown)

What stresses me/makes me unhappy? (e.g., loud noises, being touched, change of plan, too much information)

What can help calm me/makes me happy? (e.g., a strong interest, a quiet safe place to calm down, just sitting with me, giving me my own space)

How I would like you to communicate with me? (e.g., don’t ask me to look you in the eye, speak softly, use visual supports, use plain English, keep in mind that I may take what you say literally)

Who I would like you to contact?

Step 7 – Sharing my safety plan: It can be helpful to share your safety plan. This might be with a trusted friend or family member, health care professional, or support worker. Would you like to share your safety plan? Who would you like to share it with?

Storing my safety plan: It can be helpful to think about where you will keep your safety plan so that you can easily access it if you need it (e.g., printed out, in my bag, in a ‘crisis box’, on my phone). It might also be useful to think of any prompts that could help you to remember to use your plan (e.g., having a card with the safety planning logo in it in your wallet to remind you that you have a safety plan).

💕 What advice do you have for autistic midlife women to self-advocate with medical professionals?

💕 Please share any additional resources you recommend in the comments.

Hell yeah! You're awesome. This is so needed. I can tell how much time you spend on your posts, all the info you compile.

You are doing such important work. Thank you.