Content warning: if you experience fear of the dentist, please take care when reading.

TL;DR*

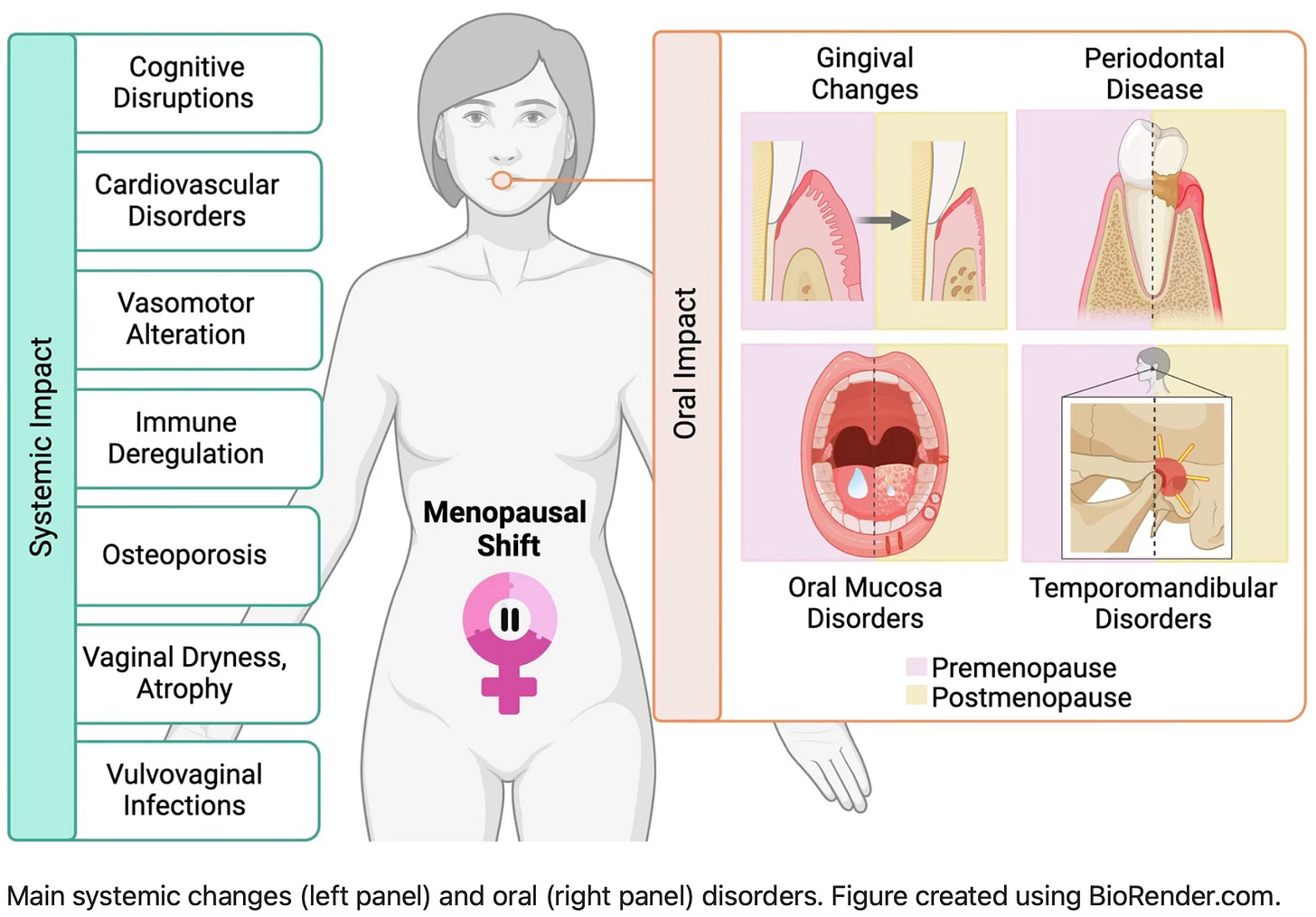

Fluctuating/reduced estrogen in perimenopause can mean bone density reduces in jaws, jaw changes, exposed teeth/receding gums leave us vulnerable to loosening/losing teeth.

Prevention is definitely better than cure, especially in the case of periodontal disease.

Avoid over brushing and under brushing.

The Goldilocks Effect may just help you avoid a gum graft.

*Guess what? I have no dentistry training, but my friend Dr Kate O’Hara, a retired dentist, has co-written the sciencey bit with me.

This post also includes links to sources should you wish to read what experts have to say on this topic.

Arriving home with a fresh, raw gum graft, having paid a fortune for the privilege, one traumatic day almost six years ago was harrowing. Fittingly, it was Halloween. My husband pulled up on the driveway, our two sons and I his passengers, returning home from Wellington late one Thursday afternoon.

In the front passenger seat, I had winced all the way home. By the time we made it 50km North up the Kāpiti Coast Centennial Highway, I was mute, silenced by surgery. Eyes wet with tears, my usual compulsive comfort eating was now out of reach. Water and smooth soups were all that was on the menu, but they would not provide the dopamine I needed in an effort to self-medicate.

It felt every bit like I was arriving home with a newborn baby, after having undergone the prolonged procedure, getting stitched back up, and nursing a tender vulnerable new existence.

My tender palate had been harvested for a wedge of soft inner tissue that was then sutured in place, attaching it over the exposed roots of my lower front teeth.

Believe it or not, it was exponentially more unpleasant than it sounds.

It took all my self-restraint to keep my tongue out of the wound so as not to disturb the sutures and compromise the attachment of the gum graft, which would have caused further bleeding and rendered the surgery pointless.

I was under strict instructions from my periodontal surgeon to seek immediate medical help should I experience any unmanageable pain, fever or blood loss. Hygienic maintenance of the site was my number one priority, in order to prevent infection.

In hindsight, as is the case with my most distressing ailments of late, periodontal disease was probably due to the culmination of decades of undiagnosed neurodivergence and undetected early perimenopause.

It was a lot to deal with, and I will spare you all the gory details. In telling you this though, I would also love to save you from requiring such a procedure by explaining what led me to the periodontist’s chair back in October 2019, aged 38.

With any luck, you haven’t previously heard about or experienced periodontal disease. I certainly wish I hadn’t.

What is periodontal disease?

Please note: The following description has been co-written with the help of Dr Kate O’Hara, late-diagnosed neurodivergent woman, perimenopausal, qualified and retired dentist.

Her explanations are italicised below. I would like to thank her for her help, I was feeling out of my depth with this section! Not to mention a little triggered by revisiting this upsetting time of my life.

Periodontal disease is a severe form of gum disease. It is what happens to some people’s gums when more common gum disease (gingivitis) symptoms go untreated, but not in everybody.

Your risk of developing periodontal disease increases with factors such as:

Genetics i.e. a family history of the condition

Poor oral hygiene

Smoking

Systemic diseases e.g. diabetes

Stress and hormonal changes

What I wish I’d understood decades ago is that plaque builds up on teeth overnight. Dental plaque is made up of bacteria, saliva, food particles and (so I have been told) dead sloughed skin from inside our cheeks. Unlike the rest of the dry skin on our bodies, it cannot flake and fall off, instead it mixes with saliva and gets trapped in the gumline.

Cleaning teeth thoroughly twice daily gives us two chances to remove plaque by flossing and brushing teeth before it forms tartar, also known by dentists as calculus.

Any remaining plaque can harden - everyone produces tartar (calculus) but at different rates, and based on factors such as:

Saliva composition and flow

Poor oral hygiene

Smoking

Diet

Tooth crowding

Having fixed retainers can make cleaning more difficult especially behind the lower anterior (front) teeth.

What types of bacteria colonise your mouth - some people carry more of the periodontal disease causing bacteria than others.

If left unbrushed and unflossed (or brushed/flossed sub-optimally) for 24-72 hours, remaining plaque may harden and become tartar that cannot easily be removed, except by a dentist or dental hygienist. The tartar can cause gaps to form between teeth and gums, under the visible gumline. This may lead to gum recession and thinning - coming away from the tooth, exposing sensitive dental roots, leaving them vulnerable to decay, and bone loss in the jaw.

This bone loss needs preventing in order to reduce the chance of later tooth loss.

These severe gum recessions are called periodontal pockets. The pockets are measured by a dentist and, at a certain measurement, may lead to a referral to a periodontist (a gum specialist).

The periodontist will assess the condition and carry out more in depth treatment which may include surgical or non-surgical deep root cleaning and gum grafting. In most cases once the condition is under control they will refer you back to your dentist and or hygienist for ongoing monitoring and maintenance.

I don’t want to upset anyone, nor retraumatise myself, by describing the procedure in any further detail.

Here is an external link to a a basic description of the procedure, including benefits and risks of periodontal surgery.

What are the common dental and oral symptoms of perimenopause?

To contextualise periodontitis as a severe and fortunately rarer gum disease, let’s firstly list what we can expect as more likely, and less risky, symptoms that can occur during the menopause transition:

Gum and tooth sensitivity

Bleeding gums

Dry mouth

Burning mouth

Altered taste

Skin thinning of gums and palate

Grinding and clenching teeth (associated with anxiety, may only occur during sleep)

Overall reduction in bone mass density, which can occur in the jawbones occasionally leading to loose and lost teeth

More information here:

Unraveling the Connection: Menopause, Peri-Menopause and Periodontal Health (Pure Periodontics)

Hormone Replacement Therapy shown to be highly effective in reducing gum disease (Oral Health Foundation)

How Menopause Affects Your Oral Health (Healthline)

Menopause and the microbiome

There is still so little known about the inner workings of women and AFABs, because history has attributed our non-male biology, anatomy and menstrual cycles to witchcraft and hysteria.

The human microbiome, not to mention all research into female bodily systems, have been scientifically explored less than outer space, which I find out of this world.

Fortunately there is now a growing research interest into the role of the female intestinal (gut) microbiome, the oral microbiome, and the role that fluctuating hormones play in the menopause transition and beyond.

Menopausal shift on women’s health and microbial niches (Nieto, M. et al., 2025) highlights that, during the perimenopausal transition, fluctuating hormone levels impact the microbiome. The changes to the microbiome communities leads to oral, intestinal (gut) and urogenital health complications and makes us susceptible to disease.

‘The gradual decline in hormone levels during perimenopause disrupts the balance of the microbiome, leading to a variety of anatomical conditions and health complications…

‘… Estrogen influences microbial communities while microbes can metabolize and influence estrogen levels. Thus, the interaction between hormones and the microbiome is complex and bidirectional. Understanding the menopausal shift encompasses how hormonal changes, environmental factors, and microbial dynamics affect menopausal symptoms and women’s health.’

Source: Maria R. Nieto, Maria J. Rus, Victoria Areal-Quecuty, Daniel M. Lubián-López & Aurea Simon-Soro, npj Women's Health volume 3, Article number: 3 (2025)

Are perimenopausal neurodivergent people more likely to develop periodontal disease?

Ha, as if anyone has researched this! Sorry - I mean, there is currently no academic research indicating correlation nor causation between neurodivergent perimenopause and periodontal disease, as far as I am aware. Because nobody has studied such a niche yet.

So, as usual, I will draw from my own lived experience of what factors I believe led to my own devastating dental demise…

London in the 1980s was an overwhelming place and time for a sensitive little redhead such as I. Born with a tongue tie that was never released, and only diagnosed on the fifth day of my second son’s life, I was born with a tendency towards gingivitis (it means “gum disease”, so no redhead or ginger jokes, thank you).

My Mum’s love language is dressmaking for herself and others. She loved to adorn me like a little doll in homemade outfits made of the prettiest scratchiest netting. I remember with alarm the tight elasticated sleeves that allowed them to puff out balloon style from upper arm to shoulder, as I cried and rapidly lost blood flow below the elbows.

I was uncomfortable in my own outfits and in my own skin.

Everything was too bright, too loud and too scary.

How did I manage the discomfort imposed on me by my very existence?

By thumb-sucking, of course! And here’s something I never tell anybody: I sucked my thumb until I was 11, and I used to keep my own stinky socks from each day and sniff them at night, tucked up under my nose, wedged in place by my thumb. Bliss. Sensory seeking, much?

There were many attempts to stop me - mustard on my thumb, bitter tasting nail-biting repellent and, of course, the warning that I was ruining my teeth.

But to paraphrase former top super model of the 1990s, Kate Moss, “Nothing tastes as good as thumb-sucking feels”.

This long term childhood stim inevitably resulted in a lifelong overbite, crowded teeth and a lisp. All of which have been problematic into adulthood, but I don’t regret thumb-sucking as a necessary self-soothing behaviour. Yes, anti-anxiety meds and an autism and ADHD assessment would have been more beneficial but, in the absence of any consideration that females could be neurodivergent, I did the best I could.

We have all found our own coping mechanisms to get us into midlife. Some days I consider taking up thumb-sucking again, when I am feeling completely overbombarded with sensory and emotional dysregulation. Sigh.

Now I know that crowded teeth are little plaque traps, and my long term “sweet tooth”self-medicating habit also made me prone to dental decay and resulting fillings.

During my childhood I developed sub-optimal toothbrushing habits, fuelled by my ritualistic undiagnosed OCD behaviours. I brushed too hard (interoception differences), for too long (no sense of time) and too often (compulsive, repetitive actions made things feel “safer”).

Maintaining my dental health in my early twenties felt like a waste of my low salary, as I was teaching and studying full time. I didn’t visit a dentist for many years, and carried on with my usual brushing technique. Flossing was a non-starter. I didn’t have time for that!

My lagging executive functioning skills made it virtually impossible to book dental appointments. Conversely, I visited the GP frequently through adolescence and into my mid-thirties, until I was diagnosed highly anxious and autistic, and realised that my constant “cancer” scares and other issues were in fact due to health anxiety, formerly known as being a hyperchondriac. (Low dose Sertraline has eased that and my multitude of other OCD and anxiety issues.)

It wasn’t until I was newly married in my late twenties that I felt compelled to initiate having my wonky teeth correctly aligned with orthodontic braces. Privately, and at great expense. My orthodontist was very empathetic, and both she and her assistant spoke with lisps and had been childhood thumb-suckers! I had found my people.

The braces were tight, awkward and painful, which I oddly enjoyed. They were endlessly difficult to floss and brush though, and they led to developing near constant sores in my mouth. The overcrowding of my front lower teeth was slow yet staggering, as they all were moved back into alignment. It was a long process.

But my eventual straightened teeth felt like a hard won battle that I wouldn’t let anything ruin!

So, to come back to the earlier question I put to myself: Are perimenopausal neurodivergent people more likely to develop periodontal disease?

I think I was susceptible to developing it due to my repetitive yet inefficient brushing behaviours. My childhood thumb-sucking stim led to the misalignment of my teeth, making it harder to eliminate plaque, thus encouraging the formation of tartar.

Thanks to self-medicating my undiagnosed teenage ADHD, I was a smoker for a short while in the 90s.

My periodontist agreed that dramatic orthodontic realignment (braces for my extra wonky teeth) may also have contributed to the periodontal pockets at my two front lower teeth that were the site of the gum graft.

Certainly my chronic sugar habit may have disrupted my oral microbiome, and that was exacerbated by perimenopausal hormonal flux, before many other more stereotypical symptoms (i.e. hot flushes and The Rage) had shown up.

I wonder if there may have been a genetic element at play? I don’t know for sure, and I probably never will…

I don’t know what it is like not to be a neurodivergent person, but I think there are elements of my way of being in the world that contibuted to my long term gum health, or lack thereof. Perimenopause was effecting me at this time in ways I had not known possible.

Perhaps future research will show that this is an epigenetic issue.

Epigenetics means that behaviours and environmental factors affect how your genes work.

In this case, where a genetic (or family history) of gum disease, alongside insufficient dental treatment and the adverse environmental factors align at perimenopause, resulting in development of periodontitis for some people. Maybe?

I posed the same question to my retired dentist friend Kate, and here is her response:

Me: In your professional opinion, are perimenopausal neurodivergent people more likely to develop periodontal disease?

Kate: That’s a really interesting question. As a qualified, now-retired dentist — and someone who is both late-diagnosed neurodivergent and currently navigating perimenopause — it’s not something I specifically tracked in clinical practice, but I also wasn’t looking for it at the time.

There isn’t yet a robust body of research directly linking neurodivergence and perimenopause to increased periodontal disease risk. But based on what we do know, my professional opinion is that the answer is indirectly, yes.

Neurodivergent individuals often experience factors that can negatively impact oral health, including:

• Executive dysfunction or burnout that interferes with consistent oral hygiene routines.

• Sensory sensitivities that make brushing or flossing physically unpleasant.

• Increased rates of anxiety or depression, which can reduce motivation or energy for self-care.

• Medication side effects (e.g., from stimulants or antidepressants), especially dry mouth — a known risk factor for periodontal issues.

• More intense or irregular hormonal fluctuations during perimenopause, which can heighten the inflammatory response in the gums.

• Genetic links — both neurodivergence and periodontal disease susceptibility tend to run in families.

• Childhood oral habits, such as thumb-sucking (more common among neurodivergent populations), that can lead to crowded teeth and make effective cleaning harder long-term.

So while we don’t yet have conclusive studies to point to, it’s reasonable to suggest that the behavioural, hormonal, and genetic factors often seen in perimenopausal neurodivergent individuals could increase periodontal risk.

Awareness, early intervention, and individualised support are key.

— Dr Kate O’Hara, late-diagnosed neurodivergent woman, perimenopausal, qualified and retired dentist.

So it wasn’t inevitable, but it seems the odds were stacked against me all along. The shame and deep despair I felt in needing the gum graft, and what I had done to let myself get into that situation were as extreme as the procedure itself.

I feel like Dr. Kate has absolved me of my guilt!

Post-Periodontal Disease Care

Following my gum graft, I had several check ups with the periodontist. “It felt like I was looking after a newborn baby”, I told him. “Well, you have looked after it very well”, he replied.

Post-surgical care was intense.

The graft was a success and remains well attached to my gumline. I was relieved to soon be discharged back to my regular dentist and oral hygienist.

I am on a frequent appointment schedule with the hygienist, around four thorough professional cleans each year.

It is expensive, but I would rather invest in preventative dental care now, than have to shell out a fortune on reactive dental surgery again in the future.

Either way, it will cost me money.

Hypervigilance around my oral health is time consuming and emotionally draining as I would never wish to go through the procedure again. I worry endlessly about the health and stability of my gum graft as though it were my third child.

Maintenance consists of twice daily interdental brushing of the gaps between all but my top front teeth, water flossing and using a pressure sensor electric toothbrush with a built-in timer with a fluoride toothpaste.

The water flosser is practically a tiny water blaster for your gumline. You can’t help but feel clean after using it - as long as you are using it properly! It features in my previous post as one of The Unsexy Gadgets That Help Me Survive Perimenopause.

I would love to know your thoughts on this topic!

💕 What changes have you noticed with your teeth and gums in perimenopause?

💕 Do you think your neurodivergence affects your oral health and dental hygiene routine?

Please let me know in the comments.

Cheers,

Share this post